TENTH EDITION OF SAVORSM

Elva Ellen Kowald

Elva Ellen Kowald

In the world of fine dining, great dishes and select wines go together. Haute cuisine – so the conventional wisdom goes – is about luminary chefs, upscale diners, starched table cloths, and discreet servers and sommeliers in hushed establishments, where it has always been thought that there is no place for the humble quaff from grain.

In the wake of the craft beer revolution, however, that notion is changing dramatically. Beer is no longer thought of as just a uniform and flavorless industrial product. Instead, it is now available in a plethora of complex and highly differentiated tastes that come in many shades of color, flavor, aroma, mouthfeel, texture, and strength. In fact, we now understand that a sophisticated brew is often a much more suitable companion to culinary delights than wine – especially when the food is hearty, piquant, fiery, or zesty like a Jaipur or Punjabi spiced chicken, a Kashmir rogan josh (lamb curry), a Bengali bhaapa maach (steamed fish), a chutney, or a Madras beef curry.

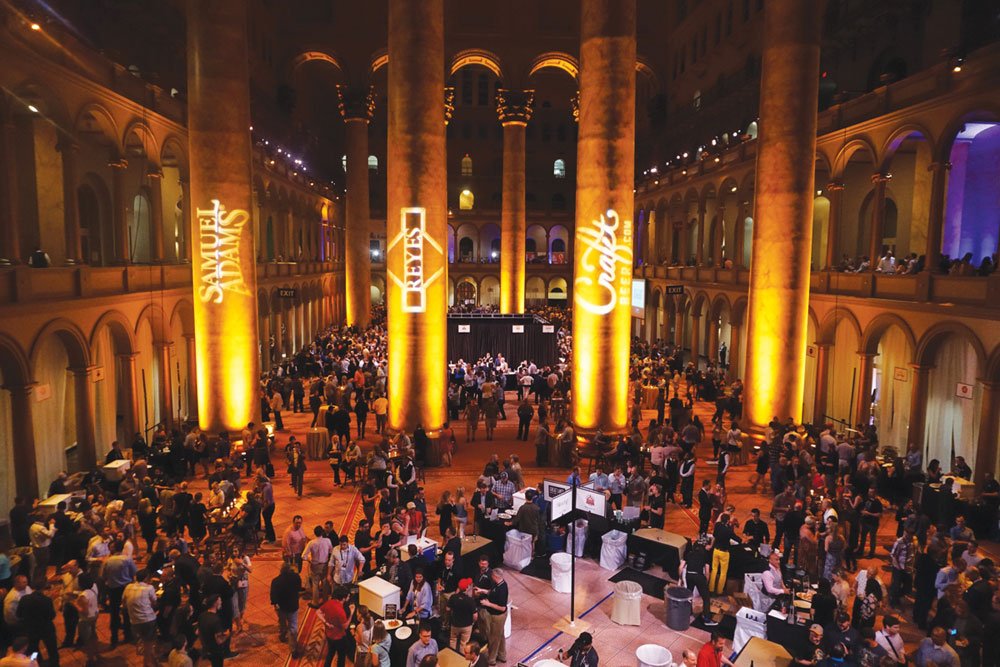

To prove the point, the Brewers Association of Boulder, Colorado stages SAVORSM, an annual beer-and-food event, in the landmark National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. There, SAVOR visitors are led on an epic gastronomic journey, with perfectly matched bites and beers in an august setting. This year, the event was held for the tenth time, on June 2 and 3; entrance to SAVOR was strictly limited to only 2,000 ticket holders a day.

The 2017 edition of SAVOR attracted 86 brewers from all over the United States; and each brewer was allowed to present two beers to the public. Along expected lines, there were many IPAs and Pale Ales on offer, as well as a few Belgian and German-style brews. But brewers had also brought many heftier, often sour brews to the museum, including Gose, Berliner Weisse, Lambic, and Flanders Oud Bruin. Perhaps surprisingly, there were almost as many beers fermented with Brettanomyces and bacteria as there were classic or traditional beers fermented just with yeast; and many of the “wild” beers were also barrel-aged.

To pair these beers with dishes was the task of the Brewers Association’s executive chef, Adam Dulye, working with a team of six chefs. These kitchen masters conjured up some two dozen eclectic and imaginative menu items that were inspired by food traditions from around the world. Among their unusual culinary creations were a monkfish served with lemon and a cold, olive-based nettle pistou; a smoked bluefish served on a bagel with cream cheese; a sweet Italian panna cotta served with rhubarb and malted oat crumble; a curried chicken served with golden raisins, apple, and walnuts; and a duck sausage served with fig and a salad of sage, parsley, and celery.

The combined efforts of the brewers and chefs resulted in some remarkable taste and flavor experiences. For instance, there was a fruited sour ale paired with ground lamb that was seasoned with onions, garlic, cumin and served with orange and yogurt. A stout aged in a brandy barrel was paired with a combination of braised oxtail, roasted shallots, fried garlic, and toasted sesame. Other examples included a wood-aged, ginger-flavored strong ale paired with an exotic coconut custard and puffed bamboo rice; as well as a Berliner Weisse paired with a lamb tartare, tamarind, and Thai basil.

It is hard to imagine a white or even a red wine standing up to these flavorful dishes. The reason why wines sometimes fail at the table is because, at their core, they are very simple. All you need for wine is grapes. You crush them and let the yeast on the grape skin ferment the resulting must into wine. Done. Beer, on the other hand, can be extremely complex, because the brewer has a dazzling array of ingredients and processes to choose from. There are literally hundreds, if not thousands, of malted and unmalted grains, hop varieties, yeast strains, and bacteria for the brewer to use in any quantity he or she wishes. The grains may be kilned, roasted, stewed, or caramelized. In addition, the brewer can use an endless variety of herbs, spices, sugars, syrups, and fruit to flavor and/or fortify the brew. Aging beer in used wine or spirit barrels adds even more variety and possibility to the final flavor spectrum! A brewer, therefore, is more like a chef than a vintner.

In other words, while wine is predominantly a two dimensional balance between tannic acidity and fruity sweetness, beer is a three-dimensional balance between acidity, sweetness, and bitterness. Beer has phenolic-astringent notes from the grain husks, the hops, and often the yeast. It may have faint hints of green apple, banana, cloves, butterscotch, hay, citrus, or pine. It often contains a full spectrum of complex malt sugars, in addition to just glucose and fructose, the two dominant sugars in wine. When trying to pair a wine with such flavorful dishes as the chefs served at SAVOR, the food often simply overpowers the drink. Beer has a much more natural affinity than wine to such foods as oily fish, strong cheese, marinated, smoked or barbequed meats, assertive vinaigrettes, or chocolate. There is hardly a wine that would not get lost next to such fruit or vegetables as avocado, asparagus, mango, tomato, or sauerkraut. Condiments like ginger, chili, mustard, and curry can “kill” just about any wine! Beer, on the other hand, can stand up to such food, because there is simply “more” to beer than there is to wine.

SAVOR was the ideal showcase for this argument. It demonstrated how beautiful beer can be; and why beer is one of the most versatile beverages in the world. As the Brewers Association craft beer program director, Julia Herz, summarized the 2017 event: “For two beautiful nights, SAVOR served as a beer pairing epicenter by pushing the boundaries of such pairings.” And one of the boundaries beer is pushing now is the gateway to fine dining. There is now no doubt that beer has found its rightful place in haute cuisine!